In last month’s column, I wrote about how the world of the artist is split squarely in two: the necessarily private creative part, and—should you wish to share your work—the unavoidably public part. And while the two parts require the same act of trust to navigate, each also has its own distinct lie that comes packaged in the benign wrapping of a question so insidious in its simplicity that some of us stop hearing it the way we cease to noticing the hum of the refrigerator. So as to give these lies their full due, I will attend to them separately—the first this month, the second next month.

As I said, the lie presents itself as a question, and what seems like a perfectly reasonable one at that: Am I any good? And what’s wrong with that question? Aren’t there Good Writers and Bad Writers? Don’t Good Writers get published and Bad Writers remain unpublished? Everyone, after all, has read writing they call “Good” and writing that they call “Bad”, and everyone wants their writing to be that which is called “Good.” Yes?

No. Because the answer to the question, “Am I any good?” is not, “No” and is not, “Yes”. In fact, there is no answer at all because the question does not actually exist. Not in reality. It exists only in our imaginations, where it is no more real than the Boogie Man.

You are exactly as Good as you must be. You lack nothing. You have everything required to write exactly what it is you want to write. Not what I want to write, or what J. K. Rowling or Toni Morrison wants to write—what you want to write. You have it all. The notion that somehow you were born tragically deficient to do the very thing you most want to do is to me as possible as an oak tree sprouting from a sunflower seed.

If, however, you want to ask a question, let it be this: Does what I have written say what I want it to say? Now that is a useful question. That is a question that will ask you to push your language to help translate what you know to be true as a feeling into what another can understand as an idea. That is a question that might send you to writing classes, writing books, or writing magazines to find clues from those who have gone before you as to how you might make a character sound as mad as you know she is. That, in short, is a question that will help you grow. Am I any good? is a question that kills, because the very question suggests the existence of a “No” you can never disprove.

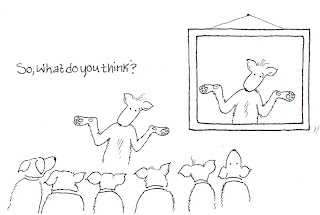

The real question, Does what I have written say what I want to say, is not always so easy to answer, however. Others might help you find a way to say what you want to say, but in the end only you can decide if you have actually said what you wanted to say. This requires trust in that most insubstantial thing—your own creative impulse. To really answer this question, you must learn to walk without the net of public opinion. This is where courage comes in. But you have that too, if you ask it of yourself.

And once you have concluded that you have said what you wanted to say to the very best of your ability—your work is done. Put down the pencil. Others will say what they want to say about it, they will like it or not, but none of that is your business. And someday you might look back at what you once wrote and feel indifferent toward it, but that is only because you have changed, and because you no longer want to write what you once wrote.

And isn’t that excellent? Isn’t life always The Next Thing? You are not a statue in the market square fixed eternally as this or that, you are a trajectory of desire bound only to that which draws you constantly forward.

More Author Articles...